The Jewish identity is kept alive through specific customs pertaining to the three most important milestones in the lives of people in the community; marriage, birth and death.

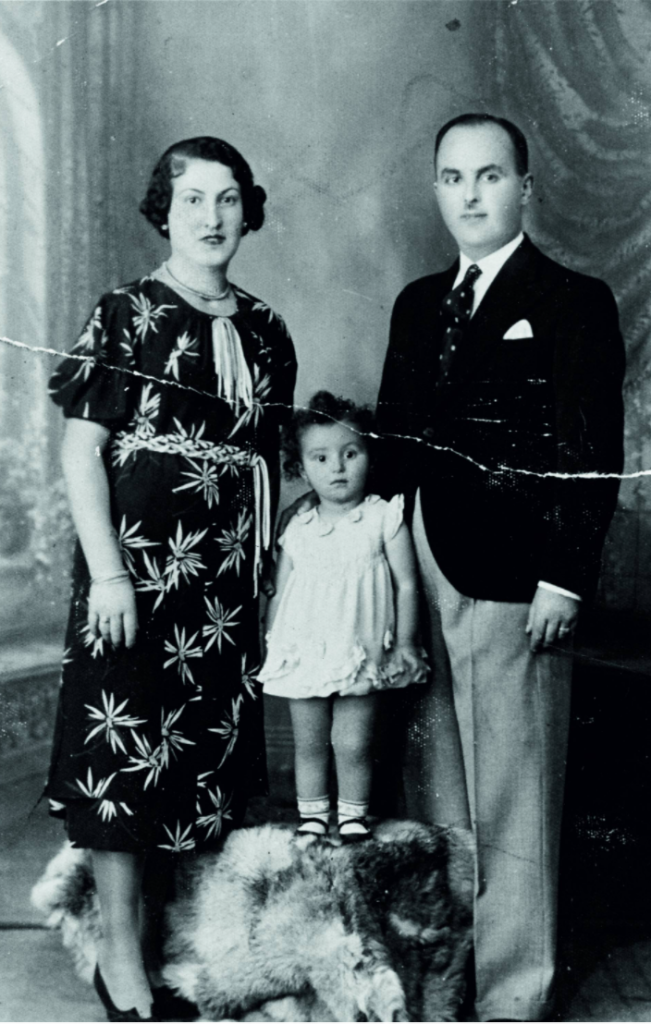

Source of the photograph: The Jewish Museum of Greece, https://www.jewishmuseum.gr

The Romaniote Jews of Ioannina maintained the demographic balance of their community by upholding strict customs regarding intermarriage which also applied to nearby communities like those of Trikala, Preveza and Corfu until the mid 20th century. In the 19th century marriages had often been arranged by young people’s parents, while until 1940 marriages made through a matchmaker were more common, with lots of comings and goings between the homes of the future bride and groom. As well as a sum of money, the dowry would include everything that was necessary to set up a new household, and these things would be displayed at the bride’s home on the Thursday before the wedding. The reading of the wedding contract, or ketubbah, was a very important moment in any Jewish wedding. The document was drawn up by special assessors and as well as giving a detailed description and evaluation of the dowry, it also made a clear statement of the marital duties of each spouse.

It was also customary for the bride and groom to exchange presents. The bride was usually given a long gold chain. Weddings took place within the first two weeks of the lunar month when the moon was waxing, but not during important religious feasts. The bride-to-be had a ritual bath, called a mikva, on the day before the wedding. It was one of the most important obligations a woman had because it left her spiritually cleansed and pure. Romaniote homes in Ioannina often had a cistern in the basement which served as a bath, or mikva. Weddings took place in the synagogue and were usually held on Sunday afternoons. The couple stood under a huppah, a canopy made of white cloth or a tallit stretched over four poles, symbolising the new household and the sacred roof.

Source of the photograph: The Jewish Museum of Greece, https://www.jewishmuseum.gr

The purpose of marriage was always to produce children. For forty days following a birth, the new mother and her newborn child were protected from evil spirits, especially from Lilith, with various customs and talismans to ward them off. In the Romaniote community of Ioannina, as in every traditional community, the birth of a boy called for a great celebration. His circumcision, or Berith Milah, took place eight days after his birth and was followed by his naming ceremony. This ceremony takes place in the home, is led by the mohel, and symbolises the confirmation of God’s Covenant with the Jewish people. There was a uniquely Romaniote custom that was observed in Ioannina. It was the writing of the Alef, the certificate of circumcision, which was decorated with wishes and prayers written in beautiful script and served the purpose of a charm for both mother and child as it hung on the wall along with a broad ribbon and florins threaded on strings. The most usual edible treat among Romaniote Jews at the circumcision celebration was the so-called fnaroh, a sweet made of eggs, sugar and honey. A small family celebration would be held at home after the naming ceremony of girls.

At the age of 13 boys became adults in the eyes of their religion. From that time on they were equal members of the community with responsibility for upholding the Law and also for their own actions. The event was celebrated with a Bar-Mitzvah ceremony in the synagogue. After the ceremony the young ‘men’ were given presents, called tefilin, which would be leather cases containing verses of the Torah, a tallit, or prayer shawl to be worn at the synagogue, a kippah or prayer cap and a siddur or prayer book for everyday use.

Finally, death is marked by simple preparations in accordance with Hebrew law, which are undertaken by the Hevra Kedoshah, a Holy Brotherhood of a voluntary and honorary nature. The close family observes a seven-day period of mourning, called the shivah. A candle lit in memory of the deceased in the home of the mourners is kept burning for a whole year.

Source of texts and photos: The Jewish Museum of Greece, https://www.jewishmuseum.gr/en/religious-life-the-cycle-of-life-part-a/ – https://www.jewishmuseum.gr/en/religious-life-the-cycle-of-life-part-b/