In addition to being religious leaders of the community, rabbis were also its administrative leaders. They found solutions to internal problems, represented the community to local authorities, answered people’s questions and were custodians of its laws and customs.

Source of the photograph: The Jewish Museum of Greece, https://www.jewishmuseum.gr

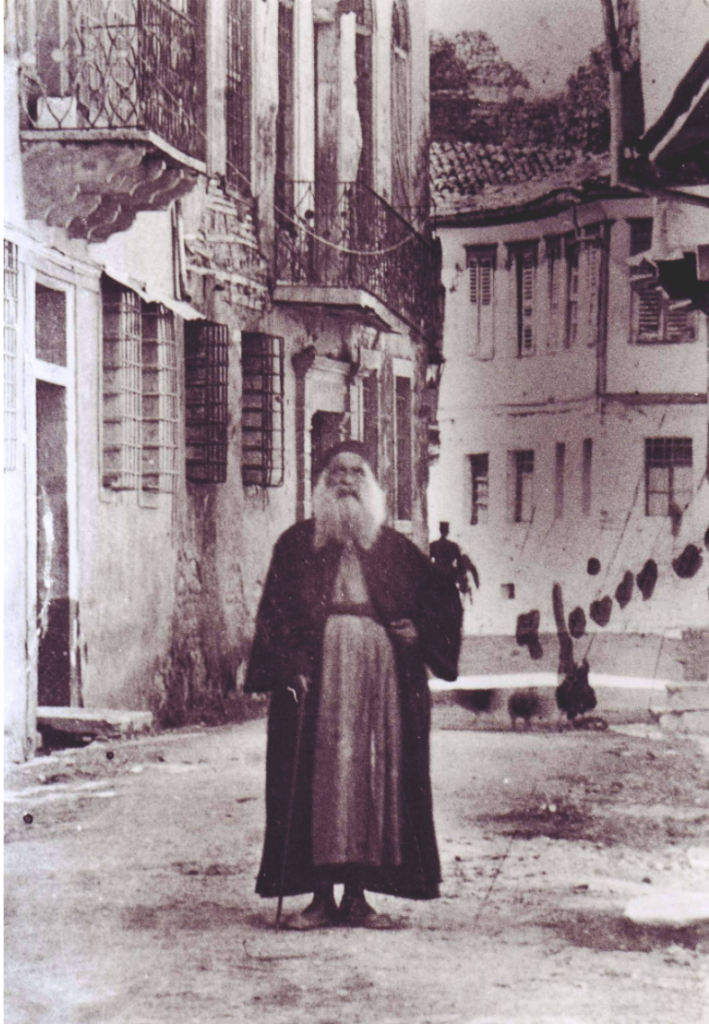

From time to time, the extremely pious Romaniote Community of Ioannina was host to renowned rabbis such as Moshe Halevi of Hebron and Itzhak Yehuda Hacohen of Safed in the 17th century, while prominent local rabbis lived there in the 19th century, during which time the standard of education in the community improved. Among these local rabbis were, Shmuel David, known as the Great haham (religious leader), and Hashmal or Haim Shmuel Halevi, looked up to as a holy figure by Ioannina’s Jews. Haham Ezra and Haham Davos were much-loved rabbis and teachers in the early 20th century.

Prayer books are essential to worship. There are two different sorts; the siddur for ordinary, everyday prayers, and the mahzor for the high holidays. There are different versions for Sephardic and Romaniote religious practice.

The Romaniote prayer book, the Mahzor Romania, was widely used among the Jewish population of Greece by the 15th century. The first printed edition was made in Venice in 1520. It was soon reprinted at Sephardic printing presses in Constantinople and Thessaloniki. It contains the prayers used throughout the year on Sabbath days and holy days and includes the piyyutim religious poems and moral-religious hymns for high holy days, as well as special Shabbat (Sabbath days) prayers and kinot laments. The piyyutim and kinot were written in fifteen-syllabic lines in Greek and bore the influence of local tradition. Also included in the book, translated into Greek but written in Hebrew characters, were the Books of Ruth and Jonah, and the Song of Songs, which were read at Yom Kippur, Shavuot and Pessah respectively. The Mahzor Romania also has a Judeo-Greek version of the prayer for the new month or new moon called Rosh Hodesh. Because of constraints imposed on printing in the Ottoman Empire, Romaniote Jews were obliged to use Sephardic prayer books, to which they added hand-written notes.

Source of the photograph: The Jewish Museum of Greece, https://www.jewishmuseum.gr

Prayer books changed over the course of time, becoming longer or simpler as the case may be. Present-day Jews in Greece mostly use the Sephardic prayer book in the form it acquired during the 16th and 17th century, based on comments made by Isaac Luria.

Hebrew religious observance has two different sets of rites and customs or minhagim, in Greece; the Romaniote and the Sephardic. They share the same basic language, Hebrew, but differ in local linguistic traits and in some finer points of worship, mainly in the synagogue.

Romaniote services are mostly in the Graeco-Hebrew form of vernacular Greek. Even to this day the few remaining Romaniote Jews in Greece, especially in Ioannina and Chalkis, use the form based on the Mahzor Romania and the Minhag Bene Roma, the Italian rite. Romaniote synagogue liturgy has its own peculiarities for each feast day. Services on important feast days, such as Rosh Hashanah and Pessah, include hymns, piyyutim, and songs in Graeco-Hebrew are added to the synagogue practice.

Source of texts and photos: The Jewish Museum of Greece, https://www.jewishmuseum.gr